A guest post.

A guest post.

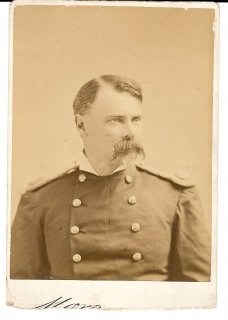

Today, we have a forgotten cavalrymen post on Capt. William Wallace Rogers by his descendant, Capt. John Nesbitt, III, formerly of the U.S. Army. Rogers served with honor in the Civil War and in the post-war Regular Army.

Captain William Wallace Rogers descended from William and Ann Rogers who immigrated to Wethersfield, Connecticut by way of Virginia in the mid-1630s, and then to Long Island, where they were early settlers of Southampton (the Southampton Historical Museum is housed in the Rogers’ mansion built on the Rogers’ homestead by a descendent of Obadiah Rogers, a son of William and his wife). William is also considered a founder of Huntington, L.I., having been one of the men who negotiated the purchase of the land for Huntington with the Native Americans. From there, their son Noah went back across Long Island Sound as an early settler of Branford, Connecticut where Captain Rogers’ ancestors resided for almost 200 years before migrating to Pennsylvania. Captain Rogers’ great-grandfather was Samuel Rogers, Jr. who served three times as a Private in the Connecticut militia in the Revolution – twice volunteering and once conscripted. This story as supported by Private Rogers’ request for his pension, and related family stories, surly was passed down to Captain Rogers as a boy, as it was to this writer and descendent of Samuel Rogers, Jr. by his grandmother a niece of Captain Rogers who was born in 1890, the year Captain Rogers died.

Captain Rogers was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, November 15, 1832, the eldest son of Minor and Elizabeth (Fretz/Fratts/Fratz) Rogers. The personal “Record of Service of William W. Rogers, Captain 9th Infantry United States Army.” dated September 24, 1883 and written down at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, says of his Civil War military service that he “Enlisted as private in Company B. 3rd Penna., Cavalry, (60th Pennsylvania Volenteers (sic)) July 23, 1861.” This was in Philadelphia. And, further, that he was “Promoted-2nd Lieutenant, Company “C” 3rd Penna., Calvalry (sic). December 31, 1861. 1st Lieutenant Company “C” 3rd Penna., Cavalry July 17, 1862.” and “Captain Company “L” 3rd Penna., Cavalry May 1, 1863.” About the time of the latter date, and before the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union Army changed the designation Companies to Squadrons for the basic assignment and maneuver elements within the cavalry battalions.

Captain Rogers further writes that he: “Served with the 3rd Penna. Cavalry in Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania from July 23, 1861 until February 6, 1864-and participated in the following named engagements.

WILLIAMSBURG, VA, May 6, 1862. FAIR OAKS, VA, June 15, 1862. Horse Killed and received injury by his falling upon my leg. SAVAGE STATION, VA, June 29, 1862. CHARLES CITY, CROSS ROADS, VA, June 30, 1862. MALVERN HILL, VA, July 1, 1862. RAPPAHANOCH STATION, VA, February 15, 1863. KELLYS FORD, VA, March 17, 1863. RAPIDAN STATION, VA, April 9, 1863. ELYS FORD, VA, May 1863. BRANDY STATION, VA, June 9, 1863. BEVERLY FORD, VA, June 1863. ALDIE, VA, June, 1863. GETTYSBURG, PA, July 2nd and 3rd, 1863. Received gun shot wounds through right breast and left shoulder, July 3, 1863. OAK HILL, VA, October, 1863. BRISTOL STATION, VA, October 14, 1863. NEW HOPE CHURCH, VA, November, 1863. PARKERS’ STORE, VA, November, 1863. (capitalization of actions are this writers for emphasis and clarity

Of the initial engagement, the battlefield of Williamsburg, May 4 & 5, 1863, Captain Rogers wrote his father in a letter of May 17, 1862 that “I saw them wounded in every imaginable manner. Some shot in the mouth, in the head, in the stomach, feet torn off and gashed in the thighs, or body, or arm with pieces of shell. Being shot myself the sight of their sufferings was awful. I soon got over it however and could look at the surgeons take off arms and legs and pile them in the field.” and described the action as follows, “Advance the charge yelling like demons or stand and receive a charge of the rebel infantry who also fought like heroes in these conflicts between infantry of both sides, the batteries would cease and yells would take the place of the thunder of guns and in this way it continued during the whole day in which regiments were nearly torn to pieces.” (Source: Curt Harley, copies of W.W. Rogers letters home to his father originally in the possession of Curt’s father Rogers Harley)

Just over a year later, the action at Brandy Station was a major cavalry battle that was a prelude to General Robert E. Lee moving North that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg. The cavalry battle at Gettysburg on the so called East Cavalry Field the afternoon of July 3, 1863, in which Captain Rogers was wounded, was both a major cavalry action and by many regarded as an important part of the Union victory that day.My interest in the Civil War goes back many years, to the mid-1950s, and was at least partially inspired by my grandmothers’ stories of the “thirteen Rogers relatives” who served in the Union Army “from a thirteen year old drummer boy, ” thorough a Rogers “who was shot but the bullet could not be removed and who died in the 1870s when the bullet reached his heart, ” to Captain William Wallace Rogers the oldest sibling of my grandmother’s mother and her twin sister who married George Harley. Even though I learned from her of Captain Rogers’ Civil War service and heroism at the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as his service among the Indian’s “out west” in the 1870s and 80s, I didn’t have any real substance to the story or his service until I came upon a newsstand copy of Blue & Grey Magazine for October, 1988. It was an “Anniversary Issue” and featured the article “Gettysburg: Cavalry Operations June 27-July 3, 1863, ” by Ted Alexander.” Therein, pages 32, and 36-39, it was related as to the action on the “East Cavalry Field” that:

At 1 p.m. ”…the artillery barrage that preceded “Pickett’s Charge” began and was distinctly heard by all the troopers.

“At 2 p.m., (John B.) McIntosh (commanding the 3rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry) decided to probe his front in order to determine the strength of his opponent. A dismounted skirmish line from the 1st New Jersey moved out about half a mile toward the Rummel farm. This prompted a counter movement by the Confederates at the Rummel farm and soon a brisk fight was underway as the opposing lines shot it out from behind parallel fence lines. Soon the Jerseymen were reinforced by two squadrons of the 3rd Pennsylvania (one of which, “L”, was commanded by Captain Rogers) and the Purnell Legion, all of which were dismounted and held the left, ”

Reading on it is reported, “Reinforcements should have meant Colonel J. Irvin Gregg’s brigade, but that would take time since it was several miles away. Custer (newly promoted Gen. George A. Custer) was nearer but heading south to join Kilpatrick near the Round Tops. Therefore, General David McM. Gregg overrode Custer’s marching orders and sent him to help McIntosh take on the Rebels at Rummel’s farm. Custer, sensing this was where the action was, did not protest.”

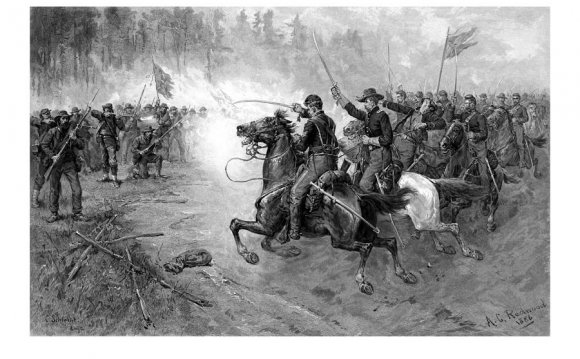

And that, “A little after 3 p.m., the Federals noticed sunlight reflecting off something in the distance along Cress Ridge. It shone from the drawn sabers of (Wade) Hampton’s and (Fitzhugh) Lee’s brigades, massed in attack formation…Lieutenant William Brooke-Rawle of the 3rd Pennsylvania recalled, “In close columns of squadrons, advancing as if in review, with sabres (sic) drawn and glistening like silver in the bright sunlight, the spectacle called forth a murmur of admiration. It was indeed a memorable one.”

Then, “As the gray riders advanced, Gregg personally ordered Colonel Charles Town to take his 1st Michigan out to meet them.” And, Town being quite ill, “…Custer rode up to lead them. The gait of both columns increased as they drew nearer, first at a trot then a gallop.”

When, “The front rank of the 1st Michigan wavered for a moment, then Custer yelled, “Come on you Wolverines!” and the entire regiment spurred ahead.”

Gregg’s troops, and in particular Custer’s Wolverines, were outnumbered by General J.E.B. Stuart’s charging legions, and, “Although the Wolverines numbered less than 500 against more than six times that many, their wedge-like penetration parted Hampton’s formation.”

INTERESTING VIDEO