On a hot Sunday afternoon in June 1876, the most notorious battle in American history took place among the remote high plains of present-day Montana.

On a hot Sunday afternoon in June 1876, the most notorious battle in American history took place among the remote high plains of present-day Montana.

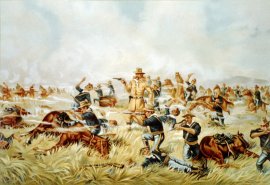

The word “battle” does little justice to the violent and brutal events of that fateful day. Suddenly surrounded by an overwhelming force of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors, 221 men of the US 7th Cavalry were swiftly annihilated. Helplessly encircled on an exposed hilltop, many of the young men fought bravely; some threw down their weapons and lay on the ground crying; others made a desperate charge down the hill to escape, only to plunge straight into the mouth of the Indian village. It made no difference. There were no survivors.

News of the disaster reached the East on 4th July, as Americans were proudly celebrating the 100th Anniversary of their independence from Britain. The realisation that the cream of their armed forces had been massacred by what were seen as primitive savages caused a deep sense of outrage as well as grief.

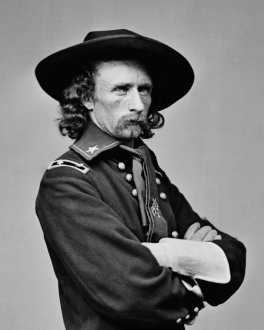

Even after the Indian “problem” had been resolved, the traumatic events of that day would leave a lasting scar on America’s psyche. The chief casualty of that was the man who had led the troops to their doom – 7th Cavalry commander George Armstrong Custer. For somebody who had always courted fame, the Little Big Horn would guarantee immortality – but for all the wrong reasons.

Custer, the man

Two things ‘made’ Custer – his family background and the American Civil War. An inveterate practical joker and risk-taker from a poor but happy family, Custer was thrust straight into the reality of war, leaving WestPoint as the North-South conflict began. Though initially frightened by action, he quickly learned that being on the front foot, being the aggressor, gave him a huge psychological advantage over his opponents. His battle philosophy rapidly developed into “Attack! Attack! Attack!” and it brought him sensational success, winning victory after victory. In a Union army beset by incompetence and failure, Custer shot to the top, becoming a ‘brevet’ General at the age of 21. He was also a celebrity with articles about the “Boy General” in newspapers as far apart as New York and London.

Life after the Civil War would be a massive come-down for Custer. Not only had the opportunity for further success disappeared, but the demotion from his temporary battlefield rank to Lieutenant Colonel was a crushing blow, one which would rankle for ever more.

Custer was not the only war hero to experience the same difficult transition to peace time but whereas other, more mature officers might gradually resign themselves to things, the young Custer, still only 25, could not. Like many young people showered with fame and success at too early an age, an over-confidence and sense of destiny burned through every fibre of his being.

Custer was not the only war hero to experience the same difficult transition to peace time but whereas other, more mature officers might gradually resign themselves to things, the young Custer, still only 25, could not. Like many young people showered with fame and success at too early an age, an over-confidence and sense of destiny burned through every fibre of his being.

The Indian fighter

Custer would forever be thought of as a great Indian fighter but in many ways this attribution was undeserved. Compared to others like George Crook, who had fought Indian tribes in the harshest of circumstances over a prolonged period, Custer saw little action against native peoples. His one great “victory” at the Washita River in 1868 was a surprise dawn raid on a sleeping Cheyenne encampment, several miles away from the main Indian village. He showed perseverance and endurance, marching through deep winter snows, and displayed daring but he would learn little from the swift “smash and grab” raid.

It reinforced the belief he had already formed that Indians were inferior fighters, preferring to scatter at the approach of the cavalry rather than stand and fight. Driving his men down the valley of the Little Big Horn eight years later, even with the knowledge that there were large numbers of Indians somewhere out of view, he had no reason to suspect that when their lives depended on it, Indians would not only stand and fight but do so with a bravery and ferocity that knew no bounds.

The Sioux War

As the officer responsible for taking his men down into the Little Big Horn, George Custer must shoulder his share of the blame, but in the decades following the battle the entire blame for the army’s campaign against the Sioux would be laid at his door. In reality Custer was a pawn in a wider game played at a higher level.

Since the origins of America, the white people had displaced and suppressed the native Indian tribes. The northern Plains Indians, especially the Sioux, were one of the last obstacles to complete control of the West. Red Cloud’s war of 1866 had resulted in outright victory for the Sioux, with the government unprepared and unequipped to invest vast resources in remote country where little was at stake. The subsequent Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had granted exclusive possession of that country to the Sioux, but the discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874 would change all that. As thousands of white citizens flooded in searching for gold and as new railway lines were being pushed from east to west, the Government abandoned all pretence of peaceful co-existence.

In late 1875 the Government ordered all free Sioux and Cheyenne to abandon the territory granted to them at Fort Laramie. They must travel east to join the reservation or they would be treated as hostile. The ultimatum would have been impossible for the Indians to comply with during the winter, even if they had been inclined to do so. As a result a major campaign involving over 2, 000 fighting troops led by three Generals, Crook, Terry and Gibbon, set out in spring to catch the Indians in a three-pronged pincer movement. If they didn’t surrender, they would be attacked.

However the area in which the Indians might be located was vast and a decision was made to send one regiment out alone to track them down. General Terry chose Custer to lead his 7th Cavalry into the unknown. An analysis of Custer’s orders from Terry has shown that the latter knew full well that Custer was being asked to take an enormous risk and that, given Custer’s track record, there was every likelihood of Custer getting involved in a fight before the other troops could arrive. Historians have struggled over Terry’s motivation in this. Was he valuing Custer’s courage or hanging him out to dry? If it all went wrong would the “reckless” Custer be a convenient scapegoat?

The Battle of Little Bighorn

Custer’s tactics in approaching the massive Indian camp on Little Big Horn were gravely mistaken. Not having any knowledge of the topography, or the precise whereabouts of the Indian camp, or any intelligence about their numbers or disposition, he charged blindly into a trap of his own making. He compounded this by dividing his forces into three, leading the 220 men under his own command straight to their deaths (the remaining forces held out against the Indians by adopting defensive positions for over 24 hours).

INTERESTING VIDEO